Lifetrack Oilbirds (Steatornis caripensis, Steatornitidae), Costa Rica.

The Oilbird (Steatornis caripensis) is one of the 918 species of birds that have been registered in Costa Rica (Garrigues et al, 2017), it’s a monotypical species as it’s the only one in its family. However this family, Steatornitidae, is related to the Nyctibiidae and Caprimulgidae, they can be differentiated in many aspects from other members of the Caprimulgiformes order, which is where these families are classified (Stiles y Skutch, 1989). In the most current update, the Auk (2016) sets this bird in it’s own order, therefor it was possible to determine that it’s very different from the taxonomy where it was previously classified. In this new order the Steatornithiformes’s only ancestor was one found in Wyoming, the Pferica nivea (Olson, 1987).

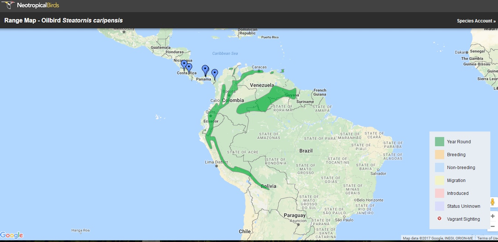

This bird can be found in Guyana, Trinidad, Venezuela, Colombia, Ecuador, Perú and Bolivia, with some sporadic registers in Central America (del Risco y Echeverri, 2011).

Fig. 1. Oilbird distribution (Steatornis caripensis). Map from: http://neotropical.birds.cornell.edu/map/?cn=Oilbird&sn=Steatornis%20caripensis&species=223931

The records of the S. caripensis in Costa Rica have been on the rise since 2009. Thanks to the gathering of data, it has been possible to determine that the species comes to Costa Rica between the months of June and September. With exception of a few records, which are records from the Natural History Museum of the University of Costa Rica and two other observations in which the dates of registration are not clear, the following are the places and years in which the S. caripensis has been registered in Costa Rica:

1.Milla Mills, 1986

2.Rara Avis (n.d))

3.Monteverde, 2010-2013-2016

4.Mirador de Quetzales, 2012

5.Turrialba, 2013

6.P.N. Volcán Tenorio, 2013

7.Barrio Luján, San José, 2013

8.Parque Internacional La Amistad (PILA), 2014

9.Corcovado, 2015

10. P.N. Rincón de La Vieja, 2015

11. Santa Rosa, Piedras Blancas, 2015

The data is from: Stiles y Skutch 1989, Bolaños Redondo et al 2015, eBird 2017. As well as from personal communications with staff members of the National Museum of Costa Rica, 2017; as well as personal observations.

Natural History:

It measures approximately 46cm, with a 1-meter wingspan. It also has sexual diphormism, in which the males are larger y are a darker shade of brown. These birds posses large vibrissae (feather around the beak) that are thought to help the bird find the eggs or chicks in the nest, these birds are monogamous. (Snow, 1976).

With nocturnal habits, it’s believed that the Oil Bird started to become different from its closer relatives due to its diet. It seems to be that little by little it started feeding off of fruit, and due to this behavior, their nests which were located on the ground became vulnerable to predation, since the regurgitated seeds made their location more obvious. As time passed by the Oil Bird started looking for safer places to nest, until it started colonizing caves. So in order to adapt to the natural conditions of these niches, the bird was forced to seek a type of locomotion that would allow it fly in conditions of total darkness (Carlos Bosque, personal communication).

The American scientist, Donal Griffin, who in 1938 was the person to discover echolocation in bats, was the same researcher who demonstrated the same evolutionary development in the S. caripensis (Griffin, 1953). The way the mechanism works is that animal sends sound waves, these waves detect objects that are in the same place as where the sound was sent, afterwards they return and go into the ear with the necessary information so that the animal is capable of recognizing what’s in front of it. Thanks to a test where the Oil Bird was placed in a dark room with obstacles, it was possible to demonstrate that as long as the bird had its ears covered, it was not able to avoid the obstacles. This was the beginning of the different investigations that have been made in relation to the ecolocation of the Oil Bird. (Carlos Bosque com. pers).

The S. caripensis is vegetarian and apparently subsists in lipid rich fruits from trees like palms, lauráceas (Stiles y Skutch, 1989) and burseráceas (Bosque et al. 1995). In fact, it’s suggested that thanks to this behavior in their diet it has allowed them to evolve different characteristics that no other bird in the world possesses, such as it being the only flying fruit eating bird with echolocation (Snow, 1979). Perhaps the most interesting ability that this bird has is precisely the echolocation which less than 20 species of birds in the world have. (Brinkløv et al, 2013).

Even though there are sporadic registers every year in our country, there is a hypothesis that it comes every three years to Monteverde in search of food. Since 2010 there are documented sightings in Monteverde where the individuals have been found eating Ocotea monteverdensis, an endemic tree of Monteverde and that can only be found in the life zone of the Humid Premontane Forest. This tree bears fruit every three years and this coincides with the arrival of this bird to Monteverde. Due to its endemism, this species of Lauraceae is endangered. Reciently Dev Joslin realized a study to find out about the abundance of this tree and found less than 800 fruiting species of the O. monteverdensis. All this suggests that by protecting these trees it might be possible to support the stay of the Oil Bird in the area.

About the research made in Monteverde.

This project was started with the support of the Max Planck Institute and the Monteverde Institute. The projects consists in finding out where do the Oil Birds that come to Monteverde come from, and where are they going. The Max Planck Institute donated 2 satellite transmitters that functioned with solar panels, each weighing 20 grams. These GPS locators where placed with a Teflon harness over the bird, and if working properly, they send a signal to the ARGOS satellite, and afterwards this signal is retransmitted to a database, called Movebank. With the signal that retransmits in the data base, it is possible to find out the location of the birds.

The place where the study was made was at the Monteverde Wildlife Refuge. Two individual were captured, the first on August 16th and the second on August 29th, 2016. The first individual had no issue flying with the harness and GPS on it, however, no data has been generated by the transmitter. While the second individual has to be freed without the GPS because it refused to fly while it had it on.

It was anticipated that the GPS would not work in its best way as it needs sunlight in order to get the energy it needs to function properly and these birds have the habit of spending the day in the caves, therefor it’s possible that the transmitters lost charge. In relation to the bird that refused to fly with the GPS on it, it’s expected that by 2019, which is the date in which the S. caripensis is estimated to return to Monteverde, a new technology will be available from the Max Planck Institute and the radio transmitter will be 4g, which is much lighter and should not affect the birds flight.

This research represents the first one that has been done with this bird species in Costa Rica, even though we haven’t gotten the information we expected, we have gotten others which will allow us to continue investigation more about its natural history. We hope to be able to understand soon where these birds come from and where they are going. It’s important to point out that this bird is very important for the forest’s ecology as it’s an excellent disperser and it’s also helping to replant and endemic species of Lauraceae in the area.

People involved so far,

Jorge Lizano, Cristian Chaves, Vino de Backer, Robert Dean, Rolando Mata, Guías del Refugio, Adrián Arroyo, Reserva Curi-Cancha, Instituto Monteverde, Instituto Max Planck, Carlos Bosque, Victorino Molina, Juan Diego Vargas, Macklin Smith, Roberto Guido, Jorge Marín, Ghisselle Alvarado, Silvia Bolaños, Selena Avendaño, Randy Chinchilla and Debra Hamilton.

References:

Bolaños Redondo, et al. 2015. Avistamiento del Guácharo (Steatornis caripensis, Caprimulgiformes, Steatornithidae) en el parque Internacional La Amistad. BRENESIA 83-84: 91-92.

Bosque, C., R. Ramírez y D. Rodríguez. 1995. The diet of the Oilbird in Venezuela. The Neotropical Ornithological Society.

Brinkløv, Signe., M. Brock Fenton., J. M. Ratcliffe. 2013. Echolocation in Oilbirds and Swiftlets. Frontiers in Physiology.

Chesser, R.T., K. J. Burns, C. Cicero, et al. 2016. Fifty-seventh Supplement to the American Ornithologists’ Union Check-list of North American Bird.

del Risco, Andrés A., y Alejandra Echeverri. 2011. Oilbird (Steatornis caripensis), Neotropical Birds Online (T. S. Schulenberg, Editor). Ithaca: Cornell Lab of Ornithology; retrieved from Neotropical Birds Online: http://neotropical.birds.cornell.edu/portal/species/overview?p_p_spp=223931. Visto el 02.02.17.

Garrigues, Richard., M. Araya-Salas, P. Camacho-Varela, J. Chaves-Campos, A. Martínez-Salinas, M. Montoya, G. Obando-Calderón y O. Ramírez-Alán. 2017. Lista Oficial de las Aves de Costa Rica – Actualización 2017. Comité de Especies Raras y Registros Ornitológicos de Costa Rica (Comité Científico), Asociación Ornitológica de Costa Rica. Zeledonia 19-2. San José, Costa Rica

Holdrige, L.R.1967. Life Zone Ecology. Centro Científico Tropical. San José, Costa Rica.

Olson, Storrs. 1987. An early Eocene Oilbird from the Green River formation of Wyoming (Caprimulgiformes: Steatornithidae).

Snow, D. 1976. The web of adatation: Bird Studies in the American Tropics. Cornell University Press.

Stiles, F.G., y A.F, Skutch. 1989. A guide to the birds of Costa Rica. Cornell University Press. New York, EE.UU.